After a year in which it has never been far from the headlines, French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo is back in the news again — this time for a cartoon that critics say pushes its provocative brand of humor too far.

The publication has sparked outrage for a cartoon that suggests drowned toddler Alan Kurdi — the 3-year-old Syrian boy whose death in September triggered a global wave of sympathy for migrants — would have grown up to be a sexual molester of the type blamed for a recent wave of mob sex assaults in Cologne, Germany.

Drawn by the magazine’s acting editor Laurent “Riss” Sourisseau — who was in the Charlie Hebdo offices last January when 11 of his colleagues were killed by Islamist terrorists — the cartoon shows two men chasing terrified women, their tongues out and arms outstretched.

Titled “Migrants,” the cartoon’s text reads: “What would little Aylan have grown up to be? (A) groper in Germany.” (When the picture first surfaced, government documents called him “Aylan,” but the child’s father has told CNN his name was Alan.)

Inset is a rendering of the famous photograph of Alan lying facedown on a Turkish beach, which was widely credited for changing attitudes toward the more than 1 million migrants who entered Europe’s borders last year, many of them fleeing conflict in the Middle East.

The cartoon references the unprecedented spate of mob sex attacks that was reported in Cologne and other European cities during New Year’s Eve celebrations, which saw hundreds of women report being sexually assaulted or robbed by men of North African or Arab appearance.

The episode has sent shockwaves through Europe, unleashing a wave of anti-migrant sentiment in stark contrast to the outpouring of public goodwill toward refugees inspired by the little boy’s death months earlier.

Racist and offensive?

The cartoon sparked an immediate reaction on social media, with many labeling it offensive and racist, and many questioning whether the masses of people around the world who tweeted #JeSuisCharlie in solidarity after the January 2015 attacks would feel the same way in light of the cartoon.

“This disgustingly racist Charlie Hebdo cartoon makes me question ‘Je suis Charlie’ in its entirety,” tweeted Australian journalist Ebony Bowden.

“I wonder how many lovers Charlie Hebdo has now?” tweeted George Galloway, a former British MP and London mayoral candidate. “A disgusting racist Islamophic cartoon of little Aylan Kurdi later…”

And Mina Al-Oraibi, an Iraqi journalist based in London, tweeted: “Charlie Hebdo latest racist cartoon dishonouring memory of poor Alan Kurdi is unforgivable.”

London-based journalist Sunny Hundal tweeted that the cartoon was “disgusting.”

But others defended the cartoon.

Maajid Nawaz, chairman of London-based counterextremism think tank Quilliam, argued in Facebook posts that critics missed the point of the cartoon, and others in the issue, as a critique of fickle European attitudes to migrants.

“Taste is always in the eye of the beholder,” he wrote. “But these cartoons are a damning indictment on our anti-refugee sentiment.”

“Stop trying to make ‘(Charlie Hebdo) is racist’ happen,” tweeted Twitter user @Chriss_m.

When contacted by CNN, Charlie Hebdo declined to comment.

Lightning rod for controversy

The weekly magazine has become notorious for its edgy, provocative approach since it began publishing in 1970.

It has long targeted politicians, public figures and religious symbols of all faiths. But in recent years the publication has gained an international profile for drawing violent blowback from Muslim extremists angered by its irreverent approach to their religion.

Even before the killings of January 2015, the magazine had been targeted by Islamists. In 2011, the magazine’s offices were destroyed by a gasoline bomb after it published a caricature of the Prophet Mohammed.

In 2006, it had reprinted controversial cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed that originally appeared in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten — a move French President Jacques Chirac called an “overt provocation.”

Earlier this month, a day ahead of the anniversary of the terrorist attack on the publication, Charlie Hebdo printed a million copies of a special edition with a cover that caused further offense to the religious.

“To us, it’s the very idea of God that may have killed our friends a year ago,” Sourisseau told CNN’s “Amanpour” program.

“So we wanted to widen our vision of things. Faith is not always peaceful. Maybe we should learn to live with a little less of God.”

L’Osservatore Romano, the official newspaper of the Vatican, labeled the cover blasphemous.

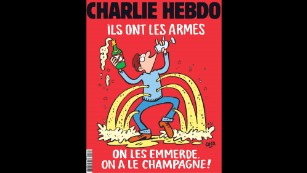

‘Screw them, we’ve got the Champagne!’

In response to the Paris terror attacks in November, in which ISIS gunmen and suicide bombers killed 130 in coordinated assaults, the magazine published a defiant cover, trumpeting the virtues of Parisian way of life over that of the attackers.

“They’ve got the weapons — screw them, we’ve got the Champagne!” it read, depicting a man gleefully quaffing wine as it poured out of holes in his body.

Speaking to CNN French affiliate BFMTV in 2012, Charlie Hebdo journalist Laurent Leger said the magazine did not intend to provoke anger or violence.

“The aim is to laugh,” he said. “We want to laugh at the extremists — every extremist. They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.”

“In France, we always have the right to write and draw. And if some people are not happy with this, they can sue us and we can defend ourselves. That’s democracy,” Leger said.

“You don’t throw bombs — you discuss, you debate. But you don’t act violently. We have to stand and resist pressure from extremism.”

As reported by CNN