New York – The icebreaker was simple: Choose a partner and learn three things about her. The catch: Your partner will pretend she does not speak.

The room full of New York City school paraprofessionals gestured and thumped the table in an exercise meant to put them in the mindset of their students: children with autism who in many cases are nonverbal.

Recent years have seen autism diagnoses skyrocketing in New York and elsewhere. There were 14,600 such students in city schools last year, up from 6,000 in 2008.

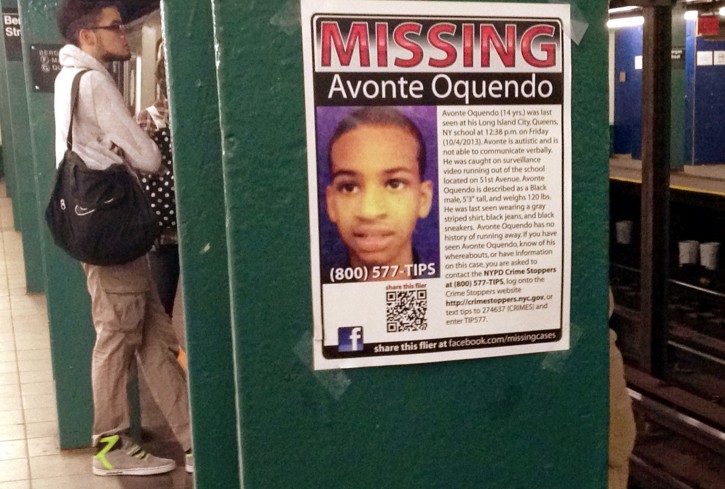

One such student, 14-year-old Avonte Oquendo, slipped out of his school two years ago and was later found dead, a tragedy that prompted the City Council to pass Avonte’s Law — legislation requiring audible alarms on doors as well as additional training to stop kids from running out of the building.

Last week’s training session at Public School 396 in Brooklyn — run by a company called Rethink, known for its videos that demonstrate therapy techniques for children with autism — was intended to help special-education workers reach children, and perhaps keep them from wanting to run in the first place.

“Why did Avonte run?” said Principal Nira Schwartz Nyitra. “We’re never going to know other than that’s something that he did. If we find other more appropriate and safer things for students with autism to do, find other ways for them to interact with their environment and their world and the people within it, then there’ll be less likelihood they’ll do those other behaviors.”

Angela Pagliaro, Rethink’s director of clinical services, showed the workshop attendees a series of videos of therapists working with children: a therapist saying “point to the dog” and rewarding the child with praise and stickers when he complies, another therapist training a boy to make eye contact by putting an object he’s interested in near her face.

The idea is to provide the paraprofessionals, who are not required to have a college degree and who typically earn around $30,000 a year — about $20,000 less than the minimum for a New York City teacher — with some of the tools used by well-paid private therapists.

Pagliaro said it’s crucial for paraprofessionals in New York and beyond to receive this type of training.

“Paraprofessionals are the last group to get training and they’re the ones that are working with students,” she said.

Marilyn Likins, the executive director of the National Resource Center for Paraeducators, based at Utah State University, agreed that more training is needed.

“Paraeducators have frequently been left out of the loop,” she said. “Do they need training? Absolutely.”

City Department of Education spokesman Harry Hartfield said the department is committed to providing high-quality services for students with autism with the help of Rethink and other contractors. “It’s our goal to ensure all staff has the knowledge and expertise they need to support students with autism,” he said.

An investigation into Avonte’s October 2013 disappearance from the Riverview School in Queens found that numerous lapses contributed to the boy’s death. Among them, the paraprofessionals who escorted Avonte’s class from the lunchroom to recess said they did not know that Avonte’s mother had warned that he had a tendency to run.

A subsequent investigation did not recommend that any employee be disciplined, and none has been. A lawsuit by Avonte’s family over his disappearance is pending.

Asked if Avonte’s mother, Vanessa Fontaine, feels that the Department of Education has improved its services to children with autism since her son disappeared, Fontaine’s lawyer, David Perecman, said, “It’s hard when you’ve lost a child to be pleased with someone closing the barn door after the horse has exited.”

Tennielle Johnson, one of the paraprofessionals who attended the Rethink session, said she followed Avonte’s story even though she was living in Trinidad when he vanished.

She said the workshop bolstered what she knows about taking care of the children she’s responsible for.

“You want to make sure they’re safe, they don’t run even if they get upset,” she said. “You use positive reinforcement.”

As reported by Vos Iz Neias