He’s a fairly young man, wearing an ill-fitting suit. His thin neck is pronounced, giving way to an equally thin face and frame. We’re meeting over a meal of sushi, something he specifically requested because it’s rare for those trapped in North Korea.

For his safety, I’ll limit descriptions of this defector. We’ve agreed that I can say he worked among the elites in Pyongyang. He is by far, the most recent defector I’ve ever interviewed; he’s only been in the free world for a year.

CNN found him through university researchers, working in conjunction with the South Korean government, who verified his status as a North Korean defector.

He stresses that revealing much more than these few details could endanger his family, still trapped in the Hermit Kingdom. He also fears North Korea could manage to hunt him down in his new life. But he’s talking to me to get a message to the West out.

He believes that among North Korea’s dictators, the dynasty of Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and now Kim Jong Un, “It is Kim Jong Un’s regime that is the most unstable. And it is going to be the shortest.”

‘False image’

The defector begins to explain why he feels that way. In 2013, Kim Jong Un’s father, Kim Jong Il, died. Kim Jong Un took over and “tried his best,” says the defector. He gave gifts, and in a public appearance, allowed his voice to be broadcast on North Korean state run television. The perception among the people was that life was about to improve inside North Korea.

“It was a false image,” he says.

n December 2013, the regime announced the second most powerful man in North Korea, Jang Song Thaek, was being expelled from the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea. Jang was accused of a litany of crimes, from obstructing the nation’s economic affairs to anti-party acts. The allegations stunned for several reasons, primarily for who the regime fingered — Jang is Kim’s uncle.

“Kim Jong Un revealed his true side,” says the defector. Jang’s arrest was broadcast on state television, followed by a statement calling him “despicable human scum, worse than a dog.” State media then announced he was executed.

Murderous rampage

The current Kim’s father, Kim Jong Il, may have tossed his people into political prisons or allowed them to starve. But he didn’t go on a murderous rampage of his own inner circle, says the defector.

Kim Jong Un took the opposite approach with his elites. Jang was just one of a number of the ruling class Kim Jong Un began to purge, as the young leader flexed his dictatorial muscles.

The outside world waited to see any fallout or any reaction among North Korea’s people. There was nothing. But within North Korea’s upper echelons, the defector says the reaction was silent but sweeping.

“I can tell you for sure the North Koreans who are in the upper middle class don’t trust Kim Jong Un. I was thinking about leaving North Korea for a long time. After seeing the execution of Jang, I thought, ‘I need to hurry up and leave this hell on earth.’ That’s why I defected.”

Risky escape

He made a risky, harrowing escape, telling no one he knew that he would attempt to defect. I’ve agreed not to reveal how he escaped, again for his safety. Suffice it to say, the chance of his capture or death was extraordinarily high.

But fear of death trying to escape paled in comparison to remaining under Kim Jong Un’s power, says the defector. After Kim’s purge of his inner circle, the defector says he witnessed a change among Pyongyang’s upper class. “They are terrified. The fear grows more intense every day.”

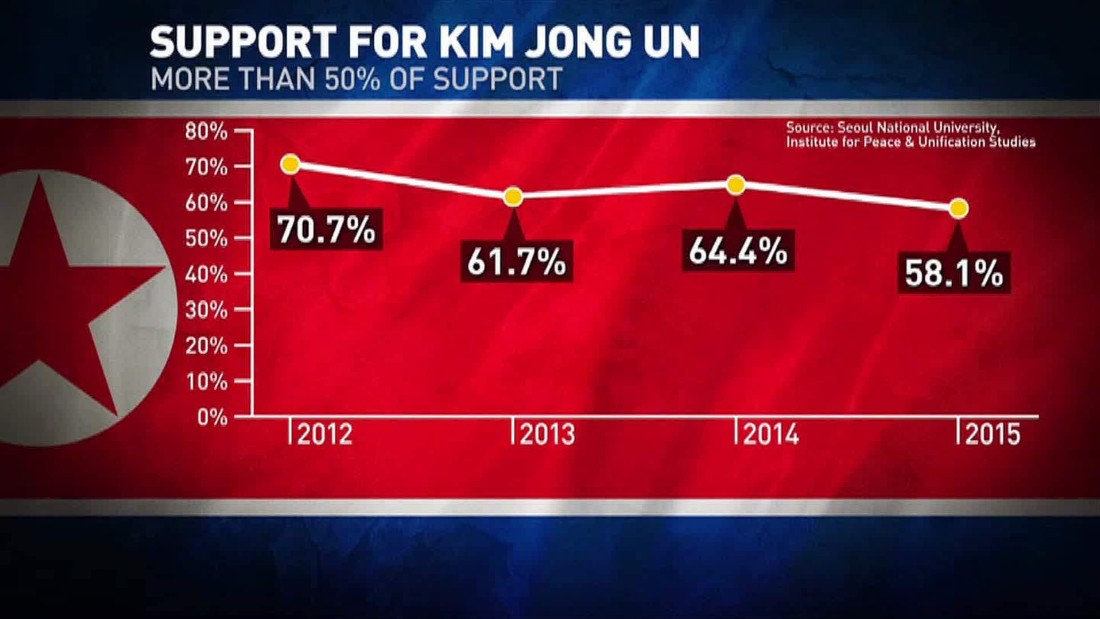

But across North Korea, support for the regime remains high, according to a survey by the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University. Since 2008, the institute has surveyed more than 100 defectors each year, the most comprehensive year-on-year examination of recent defectors.

In 2012, just as Kim Jong Un took control of the regime, defectors in the survey perceived support at more than 70%. In 2014, their latest survey of 146 defectors shows that while they perceive support of Kim Jong Un remains high, it has dropped to 58%.

The institute’s senior researcher, Chang Yong Seok, says the results should not be read as generalized facts due to the small pool of respondents. But they do also give a year-on-year snapshot of what internal support of the regime looks like.

Growing confidence

Chang believes the purging of the elites shows that “Kim Jong Un is showing confidence. It shows that Kim Jong Un is gaining confidence in his power.”

He believes the executions show Kim Jong Un is feeling more stable than the outside world perceives. But the defectors’ opinions reveal that the dictator is at risk of losing the trust and support of his power base.

“The issue is with the future. How much trust Kim Jong Un can gain from his elites after the purges. The elites could be feeling anxious. There is a possibility that their loyalty and support will weaken.”

The defector I’m interviewing is confident in his opinion that the elites’ loyalty has deteriorated and will continue along that path. He says that conviction is how he was able to leave his family behind, because he believes he will reunite with them one day.

“I can tell you for sure, the North Korean regime will collapse within 10 years,” he says without hesitation.

“Kim Jong Un is mistaken that he can control his people and maintain his regime by executing his enemies. There’s fear among high officials that at any time, they can be targets. The general public will continue to lose their trust in him as a leader by witnessing him being willing to kill his own uncle.”

The defector is guessing, of course — the same way he’s guessing someone in Kim Jong Un’s inner circle may be driven to assassinate the dictator, or that a provocation with the U.S. or South Korea will backfire on the regime.

But there is one thing that he is sure of.

“There is no collapse of North Korea while Kim Jong Un is alive. We can only expect the opening or reform of North Korea when Kim Jong Un is removed by an external power. North Korea will not collapse as long as Kim Jong Un lives.”

As reported by CNN