As Holocaust history goes on trial in Poland, files on 300,000 Nazi ‘collaborators’ in the Netherlands have already been picked apart — and publicized — for two decades

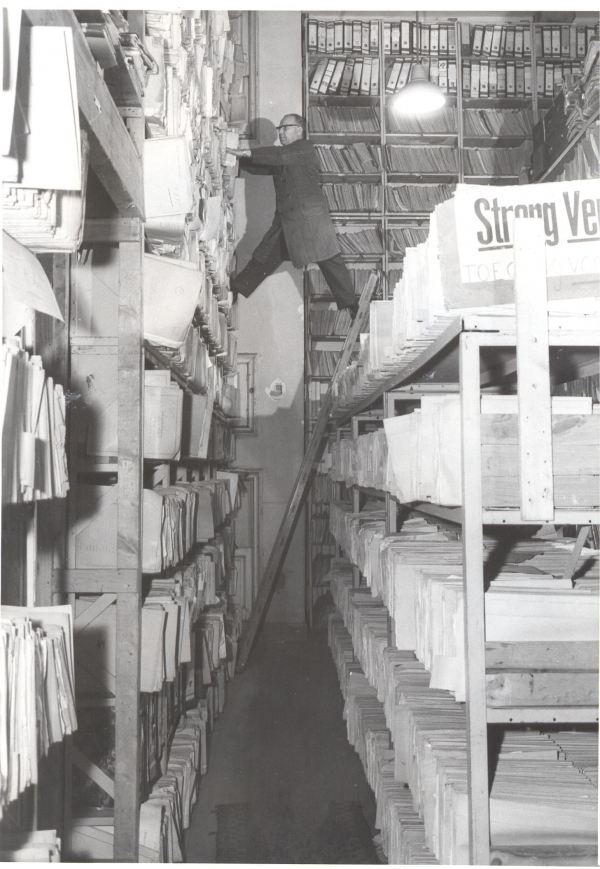

When historians seek to research what Dutch citizens did during Nazi Germany’s occupation of the Netherlands, they have access to a stack of files that’s taller than the National Mall in Washington, DC.

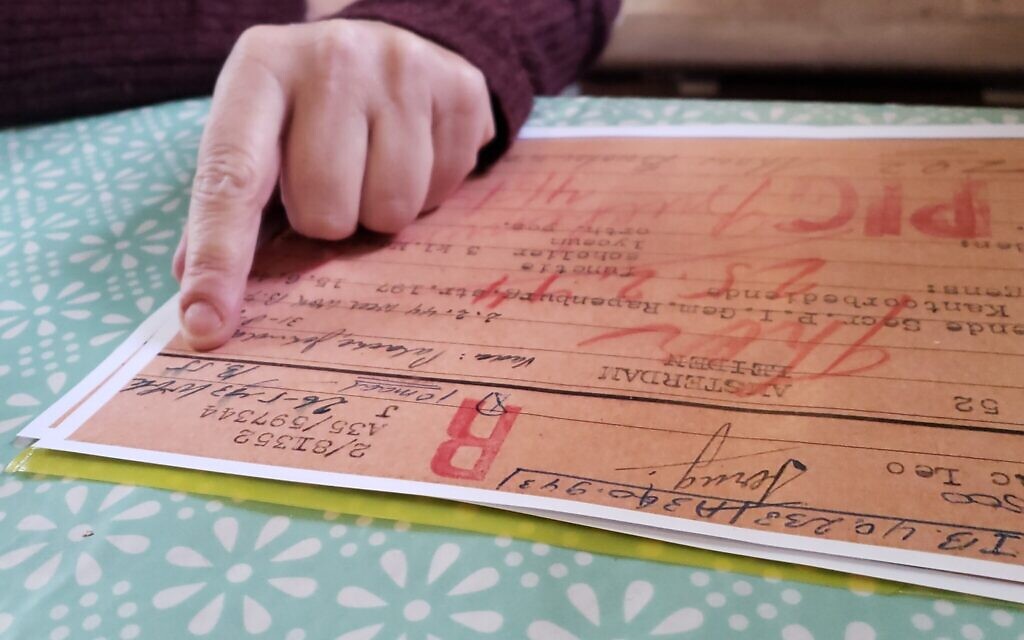

Twenty years ago, those files of the “Central Archive of Special Jurisdiction” were deposited at the Dutch National Archives in The Hague. Suddenly, 300,000 case files on Dutch citizens suspected of having collaborated with Nazis were made available to everyone.

“There are family members who want to see the file of their father or mother, but also historians and other academics,” said Bas Kortholt, a Dutch historian and delegate to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.

The climate in the Netherlands differs sharply from an allegedly “research-muzzling” atmosphere in Poland. On February 9, a district court ordered prominent Holocaust historians Jan Grabowski and Barbara Engelking to apologize to a woman who claimed the scholars slandered her deceased uncle.

At issue in the case was the authors’ book, the 1,600-page-long, “Night Without End: The Fate of Jews in Selected Counties of Occupied Poland.” The volume documents ways in which Poles collaborated with the German occupiers to persecute Jews, including the role of 20,000 so-called “Polish blue police.”

In Poland, research into the Holocaust has become a lightning rod since the Law and Justice party was elected in 2015. Simultaneously, the digitization of the Netherlands’ “special jurisdiction” archive has helped researchers piece together a diverse mosaic of Dutch citizens’ wartime behavior.

“Today some 4,000 people yearly go to the National Archives to view files,” said Kortholt, who works as a researcher at the Westerbork transit camp museum.

“Better accessibility of this archive made, makes, and will continue to make it easier to study perpetrators in the Netherlands, resulting in more academic books and fact-checking by journalists, as well as exhibitions and documentary films,” Kortholt told The Times of Israel. “All of these are needed if you want to have a healthy public discussion about a dark part of your country’s history,” he said.

Inside the Dutch archives, documents from postwar special courts and tribunals were compiled from among 150 local archives, each with its own card index. By 2025, all the files will have been digitized. If stacked on top of each other, the documents would reach four kilometers into the sky.

Since the archives were gathered and made available in 2000, many books have been published on Nazi collaborators in the Netherlands. “Hitler’s Bounty Hunters,” for example, probed the Dutch policemen who captured Jews for pay. There have also been studies of the Dutch National Socialist Party (NSB) and the 25,000 Dutch men who volunteered to fight for the Waffen-SS in the east.

‘Holocaust deflection’

Poland has its own version of the “Central Archive of Special Jurisdiction.” In 1989, files from the communist-era security services became available to the public, including those related to Nazi collaborators.

Housed at the Institute of National Remembrance, Poland’s wartime archive includes documents from the so-called “August Trials.” During the series of 32,000 trials lasting several years, “traitors to the Polish nation” were brought to justice — including 400 Poles accused of persecuting Jews.

In contrast to the trajectory of independent Holocaust research in the Netherlands, Poland’s government has sought to “legislate” use of archival material. Particularly verboten is publishing information related to Poles who helped the German occupiers implement the Holocaust.

According to Grabowski, Poland’s “History Laws” are intended to “defend the good name of the Polish nation.” Any claims that Poland bore responsibility for the Holocaust are now criminalized, despite the historian’s documentation that 200,000 Jews were murdered by their Polish neighbors.

Since 2015, Grabowski has said the Polish government is “undemocratic” and responsible for the country’s “explosion” of anti-Semitism. Leading government ministers have spoken about Polish Jews’ culpability for the Holocaust alongside political promises never to restore stolen Jewish property.

In what Grabowski has labeled “Holocaust deflection,” Poland’s government recognizes the genocide took place, but denies that “important segments of the local population” took part in murdering 3 million Polish Jews.

As documented by Grabowski and Engelking, thousands of Poles were “paid helpers” who maintained Jews in hiding. In numerous cases, the Jews were betrayed when their funds ran out. The “enthusiastic participation of Poles” in “liquidating” dozens of ghettos was noted in Poles’ personal diaries and German documents.

After the ghettos were liquidated, Poles in every county were mobilized for “Jew hunts” in rural areas. Peasants were particularly motivated to track down Jews, said Grabowski, so they could keep their newly acquired homes. Throughout the war, underground Polish newspapers “absolutely ruled out” any return “invasion” of Jews to their former homes and professions.

Even before the German genocidal machine kicked in, Polish judges, magistrates, and lawyers established the groundwork to plunder Jews of their assets, said Grabowski. Bankers and financiers worked to cancel prewar debts owed to Jews, while others made plans to plunder “Jewish gold” when the time was right.

“Extermination made being a bystander impossible,” said Grabowski. “Everyone was well aware of the genocide happening next door.”

As reported by The Times of Israel