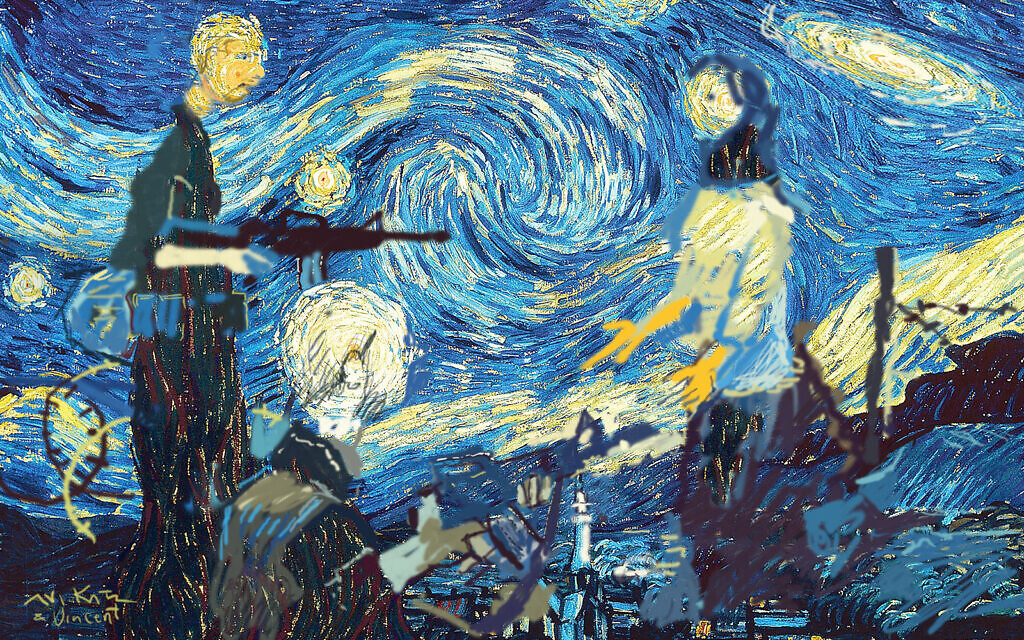

Haim Watzman’s new Necessary Story ponders love, heartbreak and the night sky as a team of IDF reserve soldiers deals with a romantic crisis in the West Bank

The girl’s fluent Hebrew did not, Nuriel thought, fit her long sleeves and head scarf. A cold October breeze ruffled her loose-fitting blouse, buttoned up to the neck and reaching down below her hips. Clearly it could not conceal a suicide belt. But when had anyone ever heard of a young woman—clearly from a devout family—in a town in the fundamentalist Muslim region of the Hebron highlands boldly approaching two armed Israeli soldiers? Her very presence in the company of a couple of hormone-soused guys who had not seen their wives for a couple weeks already could, if discovered, fatally compromise her. He meant “fatally” in a most literal way, as Muslims brothers, as is well known, believe that a sister seen with a strange man is a stain on their own honor, a stain that can only be removed with blood. That’s what Nuriel said as he kept one eye and his M-16 trained on the girl and the other on what he thought might be the constellation of Andromeda, wishing that he had not left the star map he had bought specially for this round of reserve duty on the dining room table at home.

Dani, for his part, saw no danger. The girl was clearly distressed, and while the spotlight that shone over the shin gimmel, the guard position at the gate to their lonely and dusty outpost, made everything look yellow, she seemed to be pale. She trembled, although whether from fear or the cold he could not say. Yet she had walked up the path from the road below with a sure step, even when she must have realized that she had entered the light and had been seen. When they shouted at her to halt, she had raised her hands but continued to advance, and when they shouted again, she had stopped by a large boulder and called out: “I must speak to your officer.”

They could not frisk her, as standing orders forbade touching an Arab woman. Nuriel shouted at her to go away, but she merely seated herself on the boulder and repeated: “I must speak to your officer.” It’s a diversion, Nuriel suggested, to distract us from terrorists who are penetrating the camp. He picked up the ancient, pockmarked black microphone attached to the radio set that leaned against the post on which their unimpressive red-and-white striped barrier pole hinged. Local girl at shin gimmel, he reported to Mandelbaum in the war room, demands to speak to Kodkod. Notify all posts. Dani grabbed the mike and told Mandelbaum that they were taking care of it, no need to wake Yoel. Poor guy, he told Nuriel as he tossed the mike on the radio set, has barely slept in the last 36 hours, let him be for now. He’d want us to wake him, Nuriel said. We’re not children, Dani retorted. Let’s check this out on our own. Cover me. You’re talking too loud, Nuriel cautioned. Just cover me, Dani repeated.

Dani approached the girl slowly, making sure he was attuned to any odd noises or movements in the entire compass around him. He halted about five meters away from where she sat on the boulder, her hands behind her almost as if she had been tied to the rock. Her face had beauty in it, he considered—her eyebrows were dark and narrow, and their curve was perfectly complemented by the arch of her mouth, the two separated by a small, pointed nose. He wished he could see her hair and, indeed, something more of her body.

“Our officer is not home,” he said to her, speaking slowly and enunciating his words. “We cannot help you.”

“He is indeed,” she said, in a Hebrew with virtually no accent, but somewhat stilted in its syntax and choice of words. “I viewed his jeep return just an hour ago.”

“Where is your good Hebrew from?” Dani asked.

“I studied nursing at Al-Quds University,” she said, “and lived in Jerusalem with my aunt for three years.” She pronounced the Hebrew name for the city, Yerushalayim, as if it left a bad taste in her mouth.

“How can I help you?”

“Of that I will speak only with your officer. Even if I must wait until dawn.”

“It’s dangerous for you here,” he said. “You should go home.”

“There are monsters everywhere.” She shrugged. “I will wait.”

“You will be arrested,” he said.

“I am not afraid.” But she shuddered, like a woman who sees death (or was it her lover?) before her.

“You are forbidden to get any closer,” Dani said, and walked back to the gate. Nuriel had stepped away, into the shadows.

“If we ignore her,” he told Nuriel, “at some point she’ll give up and leave.”

“You can see so many stars here,” Nuriel said. “We could see even more if we didn’t have that projector light.” He pointed. “Do you know that there is a galaxy there, even bigger than our own?”

Dani laughed. “Just last month we all went camping in the Negev with some friends. We built our tents and a campfire, ate supper, sang songs around the fire. Suddenly Leah nudged me and said, ‘Ami—that’s my twelve-year old—is gone.’ It took me nearly half an hour to find him, on the edge of a dry gully a ways outside our camp, gazing up at the sky. So I lay down beside him and followed his gaze and said, ‘That’s the North Star, you know.’ And he said dismissively, ‘I know that, Dad, I’m not looking at the North Star, I’m looking at that.’ And he pointed off to the side, where he wasn’t looking at all. And I said, ‘What’s over there, and if you’re looking at it, why are your eyes on the North Star?’ And he said, ‘It’s the Andromeda Galaxy, it’s very big and very faint, and you can only see it out of the corner of your eye.’”

Two hours later, when Amar and Sa’adon came to replace them, the girl was still on the rock.

***

Nuriel caught Kochin and Diki washing their faces at the long aluminum field sink and Brosh and Tourjeman just as they were creeping into their tent to go to sleep and relayed to them Yoel’s instructions not to get undressed until he saw what was going on. The four men protested and said that dealing with nighttime emergencies was the alert team’s job and Nuriel said that Yoel had already told him to wake up Ro’i who would be poised to rouse the alert team, sleeping in their boots, if called for, but that in the meantime the guards coming off shift would be an improvised emergency response contingent just in case something serious was going on, which it almost certainly was not. All chances were that they’d be able to go to bed in just fifteen minutes or even less. In the meantime they should wait in the war room tent, where Dani was already making coffee and Mandelbaum, who had just come back from a visit home, was offering his mother’s lemon squares, famous throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip. So, grumbling, they replaced their fatigues over their sweatshirts and trudged off to the war room and the eye-opening, heartwarming, brotherhood-inducing black nectar cooking on Dani’s camp stove.

They entered just in time to hear Dani exclaim “So you called her!” and to see Mandelbaum nod.

“Shulamit?” Tourjeman asked, settling into a battered old kitchen chair that had one short leg.

“I gave him an ultimatum before he went home,” Dani explained. “See, since we were up at 2072, when was it, five months ago, he hasn’t made a move. And I said, on this visit home you are calling her or you should not dare show your face here again.”

“Still perplexed?” Kochin grinned, eyeing the book that Mandelbaum was reluctantly closing.

“It’s a different world,” Mandelbaum mumbled.

“It’s just amazing how many stars you see out here,” Nuriel told Brosh. “I just wish I knew their names.”

“Love,” Mandelbaum said, in response to a question from Kochin.

“So what did you say to her?” Dani asked, stirring the brew. Diki hitched himself up on the folding table at the other end of the tent that served as Yoel’s office, lowered himself on his back, clasped his hands over his flat belly, and began to snore.

“I said, hi, it’s Eran Mandelbaum. From the wedding.”

“And what did she say?”

“She said, it sure took you long enough.”

“And you said?”

“I said what you told me to say, that I’d been thinking a lot about her, and that maybe we could get together for a cup of coffee or something.”

“And she said?”

“She said, you get a bus to Beit She’an, and I’ll get a babysitter for tomorrow evening.”

“And how did you feel?” Kochin asked.

“Like jelly.”

“Had you been fantasizing about her?” Tourjeman asked.

Mandelbaum gave him a sharp look. “Not that way.”

“What way, then?”

“Like, well, just about walking with her, talking to her. I dreamed about playing with her little boy. About babysitting for him when she had to go to the hospital.”

“Have a lemon square.” Dani proffered the plastic box of cookies to Ro’i, who was just coming in. Ro’i broke off half of one and went over to examine the operations log where Mandelbaum sat. The coffee foamed and Dani removed the finjan from the fire, spooned foam into his Moroccan tea glasses, poured a portion of coffee in each, and handed them out.

“She must be huge now.” Nuriel, sitting cross-legged on the ground with his rifle in his lap, carefully balanced his glass on the casing of his weapon.

“In her ninth month,” Mandelbaum agreed.

“So it could be any day now,” Brosh observed. Diki snored.

“But she’s like, well…” Mandelbaum trailed off.

“Really beautiful?” Nuriel suggested. “It’s true, Merav is most beautiful when she’s in her ninth month. It’s a different sort of beauty, from another universe.”

“So you had coffee?” Dani asked.

“In the end, no. She said she’d rather go for a walk. Beit She’an is small. You walk for ten minutes and you are out of town, in the fields. We walked and walked and she led me to this grove of trees around a pool of water. Magical place.”

“I thought you people aren’t allowed to go off alone,” Dani chided. Kochin sighed and shook his head.

“Romantic!” Nuriel sipped and nibbled.

“Did you take her hand?” Tourjeman asked. Mandelbaum reddened.

“I didn’t know if I should. But she sort of brushed her hand against mine and, well, it just happened.”

“Your first time?” Dani asked.

Brosh made room for Ro’i to share the large leather armchair with the bald spots that some previous unit had left there for posterity. “What did you say?”

“I told him, be yourself,” Dani said. “Say exactly what you feel.”

Mandelbaum tentatively opened his book. Dani reached up and slammed it shut.

“I said that, well, I really like her.” He paused.

“And?”

“And that, well, I had the feeling at the wedding that she liked me but that I don’t really understand what she wants.”

“And?”

“She didn’t say anything but her hand tightened around mine.”

“Excuse me for asking,” Dani said, “but it is an important data point for the question at hand. At this stage, did you have a hard-on?”

“Shut up,” Kochin advised.

“But we’re trying to understand if Mandelbaum is in love!”

“Just ignore him,” Brosh said. Diki snored.

“Well, I completely messed up.” He glared at Dani. “I just said the first thing that came into my head. I said, ‘Shulamit, if we get married, you will always be the number one person in my life.’ Really stupid.”

“Sounds kind of nice to me,” Nuriel said, holding out his glass for more coffee.

“What did she say?” Brosh also accepted another round.

“She leaned over and whispered in my ear…”

Yoel appeared at the entrance to the tent. “I just don’t know what to do,” he said, shaking his head.

“She said, you’ll always be number two for me.”

“What’s the story?” Nuriel asked.

“She says she wants her boyfriend back.” Yoel sat down and accepted the flared glass that Dani held out to him.

“And what’s that to us?” Brosh grumbled.

“He’s that guy we arrested yesterday, the one who threw the bottle on Ro’i’s jeep.”

Ro’i cursed under his breath. “Hit me right on the helmet. I was sure it was a Molotov cocktail.”

“She won’t see him for a long time,” Tourjeman said.

“She says that they were supposed to run away together tonight and get married. She can’t stay at home any longer. She needs him desperately. She says she’ll sit there until we bring him back.”

Ro’i shrugged. “We can’t. It’s not in our hands any more. We turned him over to regimental headquarters. He’ll go up for trial. For attacking an army patrol. He’ll probably be in for a couple years at least.”

They fell silent, as each man pondered what would, most likely, happen to this forsaken lover.

“So what am I supposed to do?” Yoel finally asked.

Dani shifted uncomfortably in his chair. “Speaking of lovers, Mandelbaum has just told us that he sat with his beloved at a magical pool and, as they gazed together at the stars, she promised him that he would always have second place in her heart.”

“What about Leah?” Brosh suddenly asked.

“Indeed,” Kochin seconded the motion. “Our discussion of love revolved around two stories.”

Tourjeman reached over and slapped Dani on the back. “You were in the doghouse. Are you out yet?”

Dani shook his head. “She just doesn’t understand. Do you know what it’s like to live with a woman who doesn’t understand you? It’s like you aren’t there. As if you were a hole rather than a presence.”

Kochin smiled. “Which woman are we talking about?”

“Leah. Leah, my wife,” Dani shot back.

“From what I hear from the guys,” Kochin said, “she’s not the one you’re living with right now.”

“He moved in with Neta?” Yoel asked in astonishment. “Why don’t you guys ever update me?”

“Try doing four hours of guard duty every night and you’ll hear everything,” Brosh advised.

“Leah is my one true love,” Dani insisted.

“Is that a premise?” Kochin asked. “Or a conclusion?”

Dani looked into the finjan, swirled what was left inside, and poured a small stream of lukewarm black sludge into his glass.

“She didn’t let up. I was exiled from the bedroom. Every so often she’d let up, there would be a few good days, and then she’d get all worked up again. It was terrible for the kids. So much tension at home.”

“And what was going on with Neta?” Kochin pressed him.

“Not good,” said Dani. “She was having a rough time. They went to Eilat together that Thursday. That night, before they go to bed, he says he’s going out for a walk and will be back soon. Then he comes back half an hour later with a Ukrainian whore and suggests a threesome.” Diki stirred and raised a bleary head on his hand to listen.

“Of course, she packs her bags, catches a cab to the airport, and flies straight back to Tel Aviv,” Dani related. “She told me all this when she showed up for work on Sunday. She was in an awful state. Couldn’t concentrate, messed up a bunch of things at work. I told her to go home and rest. She went, then came back, said she couldn’t stand being on her own.”

Brosh pressed his finger into the empty box of lemon squares to pick up some crumbs. “You told Leah about all this?”

“Of course,” Dani said. “She made as if she wasn’t listening, though. I said, Leah, this is ridiculous, she’s my work colleague, a friend, she needs my support, I can’t just ignore her. I don’t understand why you are jealous. It’s as absurd as me being jealous of Yoram. Yoram is this single neighbor who comes over to our place all the time. She said, it’s not the same thing. Why would I even look at Yoram? Do I talk about Yoram the way you talk about Neta? How do I talk about Neta? I asked. It doesn’t matter, I see it in your eyes, she replied.”

The radio crackled. Amar reported from the Shin Gimmel: “The girl is still here.”

“Maybe we should bring her inside,” Tourjeman suggested. “Isn’t she in danger? She ought to be in a shelter or something.”

Yoel shook his head. “I don’t know what to do. I’ll talk to the battalion.” He got up and stepped over to the field phone at Mandelbaum’s side and pressed the call button. There was a short conversation, first with the battalion operations sergeant and then with the deputy battalion commander. Finally Yoel put down the phone. “They say it’s none of our business. That if we take her in we’ll have her whole hamulah on top of us by morning and that the whole region, maybe the all the territories, will go up in flames.”

“Screw them,” said Tourjeman. “Let’s make it our business.”

Ro’i got up and hoisted his rifle strap over his shoulder. “I’ll go talk to her.” Yoel motioned for him to go. “I’ll come with you,” Tourjeman volunteered.

Brosh tapped Dani on the knee. “Proceed.”

“Neta was in pieces. If she couldn’t even have the love of a dork, she felt there was no hope left. I tried to encourage her. I offered to drive her home, pick her up, and pretty soon that became a regular thing. Then one day at the office, in the middle of a staff meeting, she broke into tears and ran out of the conference room. I went after her, and she sobbed that she couldn’t stand it anymore, being alone at night, that she was sure she would kill herself.”

“Uh-oh,” Nuriel said. “I see what’s coming.”

“Well, what could I do?” Dani protested. “I called Leah, explained the situation, and told her I wouldn’t be coming home for the night.”

Nuriel looked at Kochin. “Isn’t his first responsibility to his wife?”

“I’m supposed to let this fine woman kill herself?” Dani asked angrily. Then he fell silent.

Brosh shifted. “There’s something else. I can tell.”

Dani rubbed his eyes. “She said that Ami’s school had just called, that he’d gotten mad at a teacher and run away. They couldn’t find him and thought he’d left the school grounds. I love that kid so much but I don’t understand what gets into him.”

“So you went to look for him?” Diki asked sleepily.

“I told Leah that he’d be back—he always comes back.”

Nuriel shook his head. “I just don’t get you, Dani. Kochin, do you get him?”

Kochin considered. “And you still maintain,” he asked Dani, “that you love Leah, and Ami, but not Neta? I gather that you have in fact been living in Neta’s apartment since then?”

“I swear I haven’t touched her. Not once,” Dani declared, looking around at them all. “I mean, I think she wants me too. But I don’t.”

“Do we believe that?” Nuriel asked Kochin.

Kochin shrugged. “We have only the evidence of our senses.”

Dani got up noisily. “I’m going to sleep. Nuriel, you know that you and I are back at the shin gimmel at 6 a.m.? That’s the wisdom of Mandelbaum’s duty roster.”

“Wait,” said Nuriel. “We cut Mandelbaum off in the middle.”

“Oh, right,” Dani said, sitting down again. “Sorry.”

Kochin addressed Mandelbaum: “If I can read between the lines, your walk with Shulamit led you to feel that you really love her. You also felt that she loves you. But then she informed you that she would always love someone more than you. Her first love will always be her dead husband.”

Mandelbaum nodded.

“So the question is, can you love her if she also loves another?”

“That’s not the way it is in the stories, is it?” Mandelbaum said dejectedly.

Nuriel shrugged. “We don’t live in stories.”

“So you think it is possible?”

“I don’t know,” Nuriel said. “But maybe.”

Ro’i and Tourjeman appeared at the entrance to the tent.

“She’s crazy,” Tourjeman said, shaking his head and resuming his seat.

“What happened?” Yoel twisted the strap on his rifle.

“I explained to her that we want to help,” Ro’i said. “I suggested that she come into the camp, that we’d take care of her and try to convince our higher-ups to find a place she could stay until the storm blows over, or until her boyfriend gets out of jail. She refused, said she wanted no help from the Israelis who oppress her people, she just wants her boyfriend back. I told her that there’s just no way we could do that, that it’s not in our power.”

Tourjeman raised his arms and clapped his hands together on a mosquito. “I had a good look at her. I think she’s pregnant. Which would mean that she’s in real deep shit. I asked her what the story was with her boyfriend. She shrugged and said something about being star-crossed that he came from the village’s other clan, which hers has a long feud with, that they met in Jerusalem when he was working there and she was a student, that her parents and his refused categorically and ordered them to separate, and that they planned to run off to Amman, where he has a cousin, and get married there.”

“Then she started crying,” Ro’i said. “Lamenting like the Arab women do at a funeral…”

“Like my grandmother does when we don’t visit for a week!” Tourjeman laughed.

Ro’i raised his voice. “‘We were going to escape tonight! So why did he throw that bottle? Couldn’t someone else have thrown it? Is there a shortage of brave young men in our village? Why did he have to get in trouble just when we were to be so happy? Perhaps he doesn’t really love me after all?’”

“And she won’t budge. Just sits there on her rock.”

The tent fell silent.

“I just don’t know how you can really tell,” Mandelbaum finally said.

“About love, I mean.”

Dani yawned. “So the alert is over? Can we go to sleep now? Nuriel and I have to get up soon.”

“I guess so,” said Yoel. “I wish I knew what to do.”

***

When Dani and Nuriel reported back to the Shin Gimmel the five bleeps announcing the hour were just sounding from Sa’adon’s radio. The eastern sky was already lit up and the stars were gone, except for a few stragglers in the west. Sa’adon and Amar gathered up their gear. There was the sound of a car from below, clear and pronounced in the silence of the dawn. It came into view, then halted. Amar jerked his head at the girl sitting on the rock as if to say, “Still there,” and he and his friend trudged wearily off to their cots.

“Sabah al-hir,” Nuriel greeted the girl.

“Sabah al-nur,” she said softly. They followed her gaze to the car below.

Three young men emerged.

“My brothers,” she said. “Omar, Ali, and Miraj.”

“We have to get you inside,” Dani said, reaching out for her arm.

“Don’t touch me!” she said sharply.

“But…” Nuriel objected.

“If romantic love has failed me,” she said as she rose to her feet, “I must put my trust in filial love.”

She tottered, sat down quickly again, and vomited. Nuriel extended her a canteen. She washed her mouth and rose again.

“I thought a hero would save me. My hero, or one of yours,” she said. “But there are no heroes in this world.”

And she strode down the path with a sure step.

****

As reported by The Times of Israel