Researchers say the Temple Scroll, which has survived in better condition than other texts, was modified using previously unknown technology using minerals not local to the region

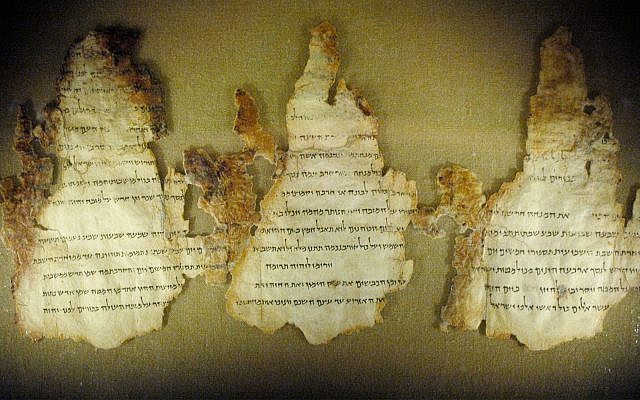

Among the thousands pieces of parchment found in caves above the Dead Sea, the one known as the Temple Scroll has stood out for its shape, color and fairly unblemished text compared to the rest of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

For years, scientists have puzzled over why the document is so different from the other documents found there and was able to survive in so much better condition.

Now, a new study has shown that the anomalous scroll was prepared using a previously unknown, ancient mix of techniques, and possibly foreign minerals, raising questions about its provenance but possibly offering clues about how to preserve the brittle collection.

All the scrolls were written on animal skins that had been stripped of hair, thinned and dried, the researchers wrote in the paper published in the journal Science Advances on September 5.

But unlike other parchments, the Temple Scroll had an added layer of inorganic material, essentially finishing the process.

Today, the scroll stands out from the rest in the Israel Museum’s collection because of its thinness and bright ivory color, which is in stark contrast to the dark hue of most of the other scrolls, due to the tanning processes used in their production. The Temple Scroll is 8 meters long and only 0.1 millimeter thick, and is considered the longest and most well preserved of the texts.

Bedouin sheepherders allegedly found the Temple Scroll in 1956 and sold it to an antiquities dealer who wrapped it in cellophane and hid it in a shoebox under the floor of his home. When scholars got their hands on it 11 years later, it had been damaged by moisture.

According to the researchers, the scroll has a multilayered structure, with the text written on an ivory-colored inorganic layer, mostly made up of salts, on the inner side of the skin (most of the scrolls have writing on the side of the skin that once had the animal’s hair).

The finding suggests “a unique ancient production technology in which the parchment was modified through the addition of the inorganic layer as a writing surface,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers analyzed the chemistry of this layer and found it to contain a range of minerals, mostly salts. While the team cannot say definitively where most of the minerals came from, they have determined that the salts did not originate in the caves and are not common in the Dead Sea region.

The processes used to produce the different scrolls were similar to both ancient Babylonian and Greek techniques, suggesting that both eastern and western parchment production technologies were used by the scrolls’ creators.

On the Temple Scroll, though, only techniques similar to those used in the West were identified, meaning it may have been produced elsewhere.

“I am not the least surprised to learn that a part of the scrolls was not prepared in the Dead Sea region. It would be naive to assume that they were all prepared there,” Prof. Jonathan Ben Dov, who was not involved in the study, told The Guardian.

Looking to the future, researchers said that understanding the minerals processes involved in creating the parchment could aid caretakers in preserving the scrolls and help identify forgeries.

The study was authored by researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and research centers in Germany.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of 2,000-year-old Hebrew and Aramaic scrolls, were found 70 years ago by Bedouin shepherds in cliffs near the Dead Sea. In total, 900 manuscripts and up to 50,000 fragments were uncovered in 11 caves near the ancient site of Qumran.

They are believed to have been written sometime between 150 BCE and the destruction of the Second Temple during the Roman conquest in 70 CE by the Essenes, an ascetic sect from that period.

Since 1967, the State of Israel has been the repository for the vast majority of the scrolls.

As reported by The Times of Israel