As head of the largest Holocaust archive in the world, Dr. Haim Gertner aims to connect other documentation centers and make all information freely available online

Dr. Haim Gertner had just taken the reins as archives director at Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center when Moshe Bar-Yuda approached him in early 2008. The Israeli Holocaust survivor wanted to see if Gertner could help unravel the mystery of his father’s wartime murder, some 66 years prior.

Bar-Yuda believed that his father had been deported from their village in Slovakia in 1942, sometime around Passover. He thought his father may have been transported to, and ultimately killed, at Majdanek, a concentration camp located on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland.

Through extensive research and bona fide detective work, Gertner was able to prove that Bar-Yuda’s father had been murdered at Majdanek on September 7, 1942. Gertner also discovered that the father’s date of birth was different from what his son had believed.

Gertner recently recalled to The Times of Israel that when he delivered these two pieces of information to Bar-Yuda, he received profound thanks.

“You brought me back my father twice,” Gertner quoted Bar-Yuda as telling him. “First, I now know his correct date of birth. And second, now I have a yahrtzeit, a day of commemoration for my father.”

“For me, this was a remarkable moment,” Gertner said. “Meeting a person that what we do for him matters.”

Gertner’s work at Yad Vashem had begun — with some reluctance — several years earlier in 2001. He had received his PhD in modern Jewish history from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and completed a post-doctoral fellowship at the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard.

Yet the scholar never planned to dedicate his professional life to Holocaust studies, initially thinking the topic was “too sad.” Ultimately, he concluded that the field was not only meaningful in relation to the past, but to the present and future as well, leading Gertner to commit himself to Holocaust education at Yad Vashem.

Over his 11 years as archives director, Gertner has overseen the tripling of the size of Yad Vashem’s trove. Today, Yad Vashem maintains the largest Holocaust archive in the world with 204 million pages of documents, 500,000 photographs, 130,000 testimonies, 30,000 artifacts, and 11,000 pieces of art.

Over the past 15 years, Yad Vashem’s “Central Database for Shoah Victims’ Names” has dramatically expanded from 2.7 million to 4.7 million individuals, based upon information gathered through new technology that meticulously combed through 10 million different entries.

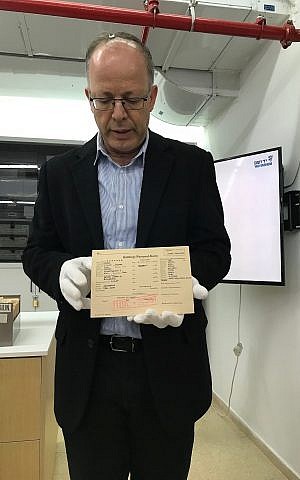

With his expressive eyes and his infectious smile, Gertner’s affable demeanor belies the somber subject matter of his work — yet he plainly appreciates the rare power of the Yad Vashem archives. It is his goal, he told The Times of Israel, to expand access to Holocaust archives around the globe.

The following interview has been edited for length.

Let’s talk about your desire to create easy access, to allow all Holocaust archives to go online. That is a massive undertaking.

[The Internet] is the marketplace today. This is where people get information about everything. This is where youngsters are communicating with each other. This is where we want to be… So we decided more than a decade ago that we would like to put everything we have freely online, unless there is a legal restriction from the owners. So we actually established, I would call it a factory, for scanning at Yad Vashem and we are scanning millions of documents every year and gradually uploading them online.

How do you work with colleagues at other institutions around the world to make sure that everyone has access to all the other documents that may reside somewhere else?

Yad Vashem is collecting originals, but tens of millions of documents are still in Europe — mainly in Europe — but also throughout the rest of the world, in North America, as well as in South America and lots of other places. So in order to collect the whole story — the fragmented pieces of this huge puzzle — in one place, we are mapping, scanning and copying all the documents that we are finding all over. And for that, we are cooperating with everyone. We are actually leading this mapping process.

If I went to Yad Vashem to find a document, but that document happens to be sitting in Warsaw, would Yad Vashem have a copy of that document, or at least know that it exists and I can either see it through the Yad Vashem website or be sent to the Warsaw archive?

First, we map. In a lot of places in Eastern Europe, it was blocked for a lot of time. In post-Communist places, for example, you can’t find in the catalogs the word “Jew” or “Jewish” so you can’t locate documents. So you have to send very, very talented groups of researchers to open almost every file and locate the information. Then we copy it. Every year, we bring to Yad Vashem between five and 15 million new scans of pages and this is why during the last decade, we tripled the amount of documents we have at Yad Vashem.

I think it is fair to say in certain countries throughout Europe today, there is some concern about blame for the Holocaust. And so certain countries are adopting rules, regulations, laws that make Holocaust blame illegal. There are ultra right-wing movements that are rising up. Is that causing challenges for Yad Vashem in terms of collection?

Yes. I am calling it the windows of opportunities that Yad Vashem has because, let’s take for example, Eastern Europe. In Eastern Europe, all the post-Communist states are building their new national identities. And it is complicated. The identity is one which is built on heroes, part of whom were involved in the murder of the Jews. So there is a huge debate in those places, so we have difficulty working there. We have difficulties working in Ukraine, in Poland, in Hungary.

When you consider that the Holocaust occurred in so many different languages, how does an easily accessible database become easily accessible?

This is one of the main challenges because we have documents in 60 languages. And we have to create a team that knows how to speak all those languages, and the technology and methodology that knows how to deal with that.

One of the ways to do that was to create a very clever database of key words — for example, first names, last names, places which have all the relevant variants of each one of the keywords… We have 1,025 options to write “Abraham” for example. You can write it in Polish, in Hebrew, in Yiddish, in Russian, in different fonts, different letters.

Is this information relevant today? Are people researching about the Holocaust through the Yad Vashem website?

I think that this is one of the most fascinating reasons to come to work every day, because in the reading rooms at Yad Vashem we have close to 10,000 visitors a year, and another 25,000 apply [to visit] every year. But 19 million people used [Yad Vashem’s website] last year. And it is growing every year dramatically, which means that it is relevant to people.

As reported by The Times of Israel