Artist John Hendrix, himself a man of faith, immortalizes theologian and anti-Nazi activist Dietrich Bonhoeffer in ‘The Faithful Spy,’ a serious comic for teens and tweens

He was a pastor, theologian, and anti-Hitler plotter — and he’s now a graphic-novel hero for teens and tweens.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s role in multiple assassination attempts against Hitler ultimately cost him his life. He is the subject of a recently released work aimed at young readers, “The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler,” by St. Louis-based author and illustrator John Hendrix.

The book combines words and images to address the moral dilemma Bonhoeffer faced when the Nazis came to power. Concerned over the increasing persecution of the Jews, Bonhoeffer decided that the commandment against murder was subordinate to the need to assassinate Hitler.

“The Faithful Spy” chronicles his subsequent path toward that goal, joining a conspiracy deep within the Nazi ranks that culminated with the failed Valkyrie attempt in 1944 and Bonhoeffer’s imprisonment and death at the Flossenburg concentration camp in 1945.

Although this may seem like somber material for the intended age range of 10 to 14-year-olds, Hendrix believes they will be up to the task.

“Young people love stories about when moral stakes collide,” he said. “To feel true to someone, have them work together — kids are starting to do that, come out of the black-and-white period and see that there are grays in the world.”

He added, “I think children are very resilient thinkers at that age. They don’t have clear answers. I think we should give them stuff to encourage them to continue thinking.”

Hendrix has been thinking about Bonhoeffer for some time now, first reading his theology in college.

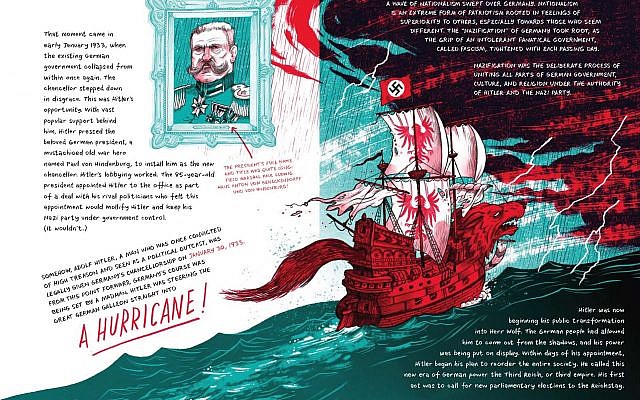

“I’ve always loved his writing,” said Hendrix, a practicing Christian. “His story stayed in the back of my mind. When I got into publishing, I thought, ‘Man, it would be a good story to tell from a faith angle,’ how Germany descended into hate, the rise of the Third Reich and the church’s response.”

Hendrix never considered following a traditional picture-book format, which was his usual method at the time, but was sure that a graphic novel was the perfect format for the subject matter.

He worked on the book over a five-year period — including traveling to Germany in 2016, where he sketched sites vital to Bonhoeffer’s life, such as Zionskirche in Berlin, a church where he ministered and pastored; and the Flossenburg concentration camp, where he was killed shortly after his 39th birthday, just a few weeks before the camp’s liberation. Today, a chapel at Flossenburg honors Bonhoeffer and other Holocaust victims.

“It was a very somber visit, pretty incredible,” Hendrix said.

To tell the story of Bonhoeffer’s life for young readers, Hendrix called upon his multitude of skills as both an artist and writer, which served him well in previous works with subjects from Jesus to 19th-century American abolitionist John Brown.

“I think what I bring to a book like this is an unusual kind of visual experience,” he said. “It’s neither one nor the other, word nor picture, a hundred pages of both, a visual novel.

“The opposites of words and images work well together when paired. A third thing results, neither word nor image — a gestalt, really. The sum is greater than its parts,” he said.

A cartoon version of Bonhoeffer — unassuming, bespectacled, balding, quietly heroic — is counterpoised against Hitler, who is shown as an arrogant, menacing, destructive villain. Much of Bonhoeffer’s dialogue consists of his actual quotes; Hendrix viewed all of his original letters while in Berlin.

Hendrix found many other means through which to tell the story, from the allegorical to the technical.

Animal metaphors abound: the Nazis are depicted as rats and Hitler as a wolf. “Adolf” means “noble wolf” in German, Hendrix points out, but his lupine Hitler is “not heroic or brave but savage, cunning.” (Animal metaphors were also used in perhaps the most famous graphic novel about the Holocaust: Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” where Jewish mice were at the mercy of Nazi cats in the concentration camps.)

“The Faithful Spy” also features biblical imagery, representing Bonhoeffer as David with a slingshot, confronting a Nazi Goliath with a swastika on its shield. The accompanying text reveals Bonhoeffer’s “holy anger” at Hitler:

“He believed an attack on the Jewish people was an attack on all of God’s children.”

Hendrix called the David and Goliath illustration “probably” his favorite in the book, and it aptly depicts the struggle that developed between Bonhoeffer and the Nazis.

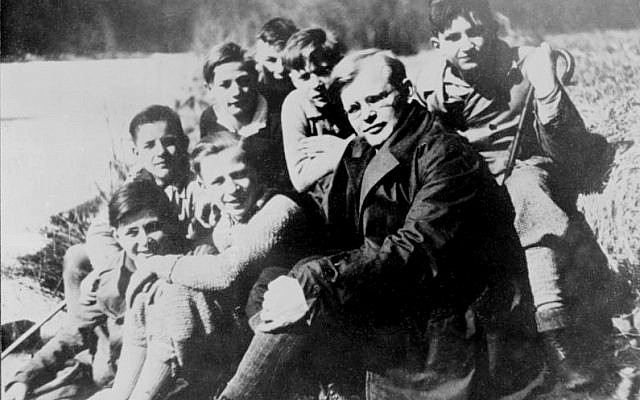

Born in 1906, Bonhoeffer grew up in a large, accomplished family that nevertheless knew tragedy; one of his brothers, Walter, died fighting for the Kaiser in World War I. Bonhoeffer came of age in a backdrop of German defeat and Nazi vengefulness.

In the 1930s, the young theologian wrote two acclaimed works, “The Cost of Discipleship” and “Life Together.” Both, according to the graphic novel, “further explored his long-debated question: ‘What, exactly, is the church?’ and ‘How does the church love ‘the other?’”

With the rise of Hitler that decade, Bonhoeffer came to feel that many in the German church were betraying God through acquiescence with Nazi doctrine against “the other,” including anti-Semitism.

“Christians in his church who were of Jewish background could not come to church,” Hendrix said. “It seemed crazy [to Bonhoeffer].” And “it was clear to him,” Hendrix said, that such policies “did not have biblical mandates.”

Bonhoeffer voiced his concerns in a 1933 essay, “The Church and the Jewish Question,” but “everything started to escalate,” Hendrix said. “The stakes got higher.”

This included the 1938 pogrom of Kristallnacht. Hendrix depicts the English equivalent of the term — “The Night of Broken Glass” — in letters consisting of broken glass. After the outbreak of World War II, Hitler stunningly conquered France through the blitzkrieg campaign, shown in a map by Hendrix. Bonhoeffer found himself facing a rapidly more powerful enemy that controlled both church and state.

The “major theme” of the book, Hendrix said, is Bonhoeffer’s reaction to “the church’s capitulation to Hitler” and what was happening to the Jews. He embarked on “a counter-narrative,” Hendrix said, one that showed “there were good people in Germany who saw what was going on, tried to change things and ultimately failed.”

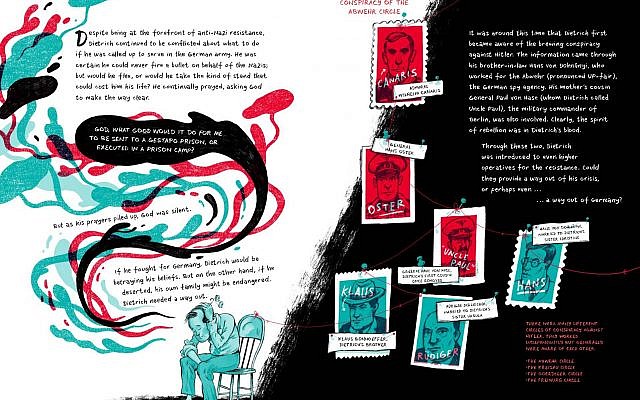

As the book demonstrates, Bonhoeffer used family connections to join an anti-Nazi network in the Abwehr, or German intelligence agency.

Pretending to be working for the Nazis, he actually participated in counter-efforts, helping 14 Jews escape to Switzerland in 1941 and documenting Nazi atrocities.

And, Hendrix said, “There were many assassination attempts [against Hitler]. They did not go well. It’s new to a lot of people. I picked three [to illustrate] by the inner circle around Dietrich that were closest to actually happening.”

The second such attempt, a bomb placed on a plane, resulted in Bonhoeffer’s imprisonment at Tegel Prison in Berlin in 1943. Hendrix depicts his life in cell block 92: a poignant romance developing with Maria von Wedemeyer, the granddaughter of one of his supporters, who made visits and smuggled in information; Allied air raids on a nearby machine-works factory in which he comforted fellow prisoners; moments when he doubted the existence of God.

The conspiracy continued, culminating with Operation Valkyrie on July 20, 1944.

“Pick an assassination plot and most people probably know the Valkyrie one more than others,” Hendrix said of the attempt to detonate a bomb beside Hitler in his stronghold, the Wolf’s Lair.

Comic-strip panels show the 12 agonizing minutes of putting the plan into action — with the explosion dramatically depicted on the following two-page spread.

“I thought it was a very exciting, challenging arrangement,” Hendrix said. “The story worked well when it felt kind of like an action story.”

Hitler escaped death and began a wolf-like hunt of the conspirators, which proved fatal to Bonhoeffer when key evidence was found against him, leading to his transfer from Tegel to three far harsher destinations: an SS prison in Berlin, the Buchenwald concentration camp, and finally Flossenburg, where he was executed on April 9, 1945 after delivering his last sermon.

Hendrix said that it was “very difficult” to decide how to illustrate the ending of the story.

“I didn’t know how to end,” he said. “I had different versions. I did not make any one idea too important.”

The story might have had quite a different ending had Bonhoeffer survived.

“It was close,” Hendrix reflected. “He was a couple weeks from the camp being liberated. I wonder about that often. Does his legacy change if he survived?”

Had he lived, Hendrix said, “he would have probably written other works. We would still know him as a theologian. I think his sacrifice partially vaulted his status as a hero from the war.”

It’s a story that Hendrix hopes will have lasting lessons for young readers.

“I think there are a lot of angles, even if you’re not interested in faith, or the faith story of Dietrich,” Hendrix said. “It’s a fascinating tale of what it means to resist, hold ideas at personal risk.”

As reported by The Times of Israel