The 41st president beat AIPAC, but lost 24% of his Jewish backing after confronting Israel over the settlements; it’s a lesson US leaders since have taken to heart

WASHINGTON — Former Israeli ambassador to the United States Michael Oren once castigated Barack Obama for not abiding by the principle of “no daylight” and “no surprises.” That was most reflected, the Israeli diplomat emphasized, in Obama’s publicly castigating Israel’s settlements.

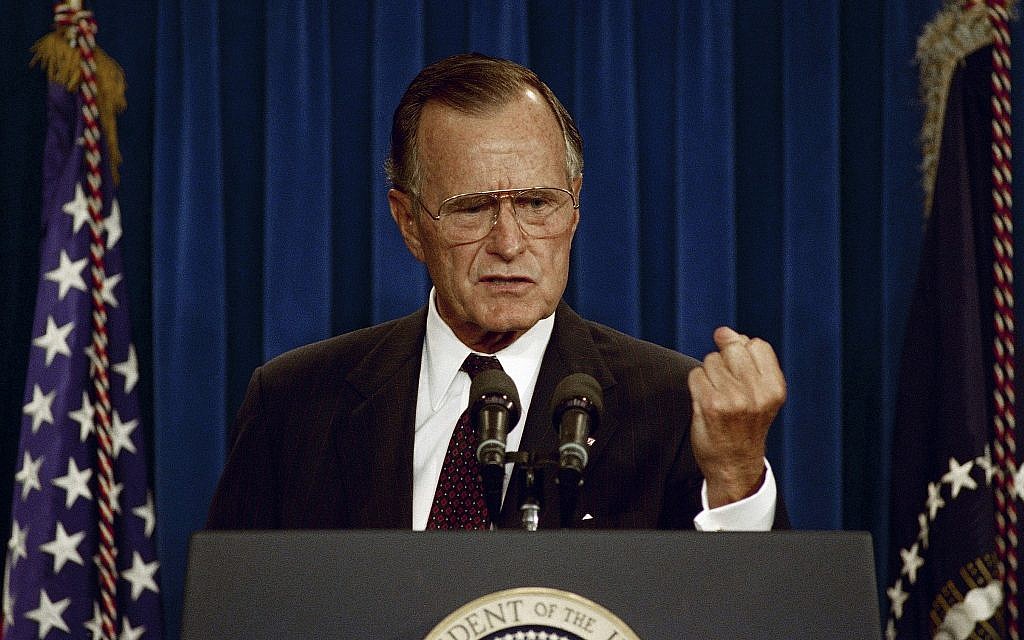

But Obama was not the first president to make Israeli settlements such a point of contention. Former president George H.W. Bush, who died Friday night, went much further than him, in fact.

Bush, who was president from 1989 to 1993, forever changed American politics when he exerted his power to curtail the settlement enterprise and faced a vehement backlash.

He made clear the cost of an American president waging a political fight against the vast coalition of pro-Israel lobbying groups. In doing so, he exposed the limits of what the world’s most powerful man can do when trying to solve the world’s seemingly most intractable conflict.

One of the most controversial moments of his single-term presidency was when he delayed Israel loan guarantees until it halted its settlement building in the West Bank and Gaza and entered a peace conference with the Palestinians, what would later became known as the Madrid Peace Conference.

The United States had previously agreed to provide Israel $10 billion in loan guarantees to help Soviet Jews resettle in Israel. But in September 1991, Bush said that the United States would not issue those guarantees until former prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir agreed to those demands.

“It is in the best interest of the peace process and of peace itself that consideration of this absorption aid question for Israel be deferred for simply 120 days,” Bush told reporters. “I think the American people will strongly support me in this. I’m going to fight for it because I think this is what the American people want, and I’m going to do absolutely everything I can to back those members of the United States Congress who are forward-looking in their desire to see peace.”

That set off a bitter political fight on Capitol Hill, with pro-Israel organizations, most notably the powerful American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), seeking to muster enough Congressional support to override the president.

During that quagmire, Bush famously complained that “there are 1,000 lobbyists up on the Hill today lobbying Congress for loan guarantees for Israel and I’m one lonely little guy down here asking Congress to delay its consideration of loan guarantees for 120 days.”

The notion of the president — leader of the world’s only super power — as “one lonely little guy” going up against the pro-Israel lobby has become a staple of the narrative that Israel backers wield excessive power in the country’s political system.

But it’s worth noting that, in this particular battle, the US pro-Israel lobby didn’t win its fight against the American president.

Bush at the time enjoyed a 70 percent approval rating. While the American Jewish community was mobilized on the issue, it was not prepared to declare all-out war on the popular president over it. AIPAC and Congressional leaders dropped the fight over the 120-day delay. Eventually, Bush’s diplomatic efforts worked and Israel entered the Madrid Peace Conference in October 1991.

While an undeniable achievement for Bush, that episode was not without its costs. Bush’s backing by American Jews took a nosedive immediately thereafter, despite his landmark support for helping Jews escape trouble spots around the world, from Russia to Syria to Ethiopia.

Receiving 35% of the Jewish vote in 1988, Bush only got 11% in 1992, when he lost to Bill Clinton. Only one Republican nominee for president has received a smaller portion of Jewish support — when Barry Goldwater claimed just 10% in 1964. Roughly 25% of American Jews voted for Trump in 2016.

Bush’s defeat in 1992 was not mainly because of his contentious relationship with Israel. Rather, Clinton seized the economic frustrations of American voters. “It’s the economy, stupid,” Clinton’s adviser James Carville famously said.

But American presidents have since been cautious to avoid paying for challenging Israel like that — and none really has, especially not in their first term.

Bill Clinton made sure to abide by the principle of keeping differences with Israel private; and he certainly had differences with Netanyahu during the Israeli premier’s first go-round from 1996 to 1999.

George W. Bush, the elder Bush’s son, was careful not to criticize Israel during his first term, which took place during the Second Intifada. But after he won reelection, he spoke out against Israel occasionally, including on settlements. He was also the first president to call for the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

While Obama had a difficult relationship with Netanyahu early on — his calling for a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders with swaps, his pressing Netanyahu to back two states and freeze West Bank settlement construction — he saved the biggest fight for his second term: brokering a nuclear agreement with Iran that Netanyahu and virtually all of Israel hated.

It was not until the very end of his presidency that Obama allowed the passage of a UN Security Council resolution that criticized settlements, protecting Israel with his veto throughout the first 7.9 years of his time in the White House.

The fact that he waited until his last days in office, despite an increasingly acrimonious relationship with the Netanyahu administration, was a sign that Bush’s hard-learned lesson has continued to reverberate in Washington.

As reported by The Times of Israel